It was 9pm when my friend dropped me off at the Bart station. On our way there, she expressed concern for my safety because “the neighborhood isn’t so safe.” While I had been at this station many times before, my friend’s worry perked up my nervous system. Through the turnstile and down towards the flickering lights and dimly lit tracks, I found one other person waiting for the train: a scruffy man in tattered clothing slumped over a bench. When he noticed me, he decided to spark up a conversation. I put my phone away and answered politely but decided to stay a distance away. Because the trains were loudly zooming by, he got up from his seat and swayed towards me to hear me better. I calmly shifted my stance to face him, took my hands out of my pocket and began to note all the soft strikeable spots on him. Even though I stayed calm, I was ready to make my move if the man got too close or motioned to touch me. Luckily, the train arrived. As we walked through the doors, he turned to nod a farewell as he walked over to his seat. It was then that I noticed that the man had a severe curve in his back, which resulted in a limp. In the full light of the train, I saw the frailty of this man. I realized then that it was me who was intent on causing harm. I can still remember the imagined satisfaction of my hands striking and landing on his body.

“I can still remember the imagined

satisfaction of my hands striking

and landing on his body.”

Maybe my friend had colored my perception that evening, but it’s possible anyone could have made that same mistake given the circumstance. Women are often leery when entering environments alone: walking to their car in a parking lot, on their way home from a late dinner, or riding a taxi. As a woman who studies and teaches kung fu, it is not lost on me that most martial art schools like to use the term, “self-defense” to market to women. And why not? Afterall, women are statistically more vulnerable to violent crimes than men, particularly sexual violence. The issue here is not that we don’t have the right techniques to get out of the situation. The issue is that women are expected to dismiss their own concerns to accommodate the comfort of another. A friend, who worked with victims of violent crimes, shared that women who were attacked in an elevator ignored their gut feeling about another passenger. Even though their instincts told them not to enter, they were more worried that they would offend the person who eventually attacked them.

“The issue is that women are expected to

dismiss their own concerns [of safety] to

accommodate the comfort of another.”

The pedagogy of self-defense often involves simulating attacks. While I understand its utility in responding to physical altercations, this method runs the risk of retraumatization for some and it’s simply not enough for the rest. I believe women take self-defense classes because they just want to feel safe wherever they are and wherever they go. However, a safe space isn’t a location. It’s not necessarily a dark alley, or an empty parking lot. One can feel unsafe in an office building amongst coworkers, walking on a busy sidewalk, or even at home with an abusive partner. The majority of perpetrators of sexual assault come from people the women knew, either intimately or casually. Moreover, the subtlety in how offending men treat women is not something that can be kicked or punched away: an offhand remark, unsolicited/unwanted “friendly” touch, or long glances at our bodies. A lot of men have not done the necessary, deep dive work to dispel the patriarchal and often oppressive standard that we all grew up in. It is most often the women who are the ones doing this work.

“a safe space isn’t a location…

…One can feel unsafe in their office…

walking on a busy sidewalk, or even at home…”

The way I view self-defense changed when the women in my kung fu school started to gather every month. Initially, it was a way for us to train together because there were so few of us, but it ended up becoming a support system. I recall having a discussion about one of the practitioners in our school. One of the women brought up how uncomfortable she felt around a particular person. What empowered her was not advice on how to respond, it was validation on how she felt. We had all felt some degree of discomfort around this person but we had all kept it to ourselves because this person had not done anything overtly offensive. He was rather nice or “helpful,” but we couldn’t shake the feeling of discomfort when he was around. Up until that point, she never felt safe enough to share what we all felt. For some reason, there was no room for it during training time or even when spending time with the larger kung fu community. It was in the company of other women that this was able to happen. What we all discovered for ourselves is that in the martial arts school – as much as anywhere else, is an underlying attitude of misogyny. Whether we know it or not, this attitude is ingrained in our society, and it has even been written in our laws. That’s what makes us feel unsafe. It’s for this reason that I think many martial arts schools have implemented women only classes in their schedule. While it is a good start in creating welcoming spaces for women, it does not place any responsibility on the men to do the same, excusing them from doing the work.

“the subtlety in how offending men treat women

is not something that can be kicked or punched away..”

I think that the confidence we gain from taking self-defense classes isn’t from the techniques. Rather, it’s the opportunity to strike at something with all our might. For women, this wasn’t encouraged when we were younger. Beginners usually laugh at the discomfort of having touched their rage, but women need to have access to that sort of energy to assert themselves: physically and verbally. More effectively, however, is how the teacher and martial arts school attend to issues that women face regularly. For example, does the school or institution have a policy against harassment and are the consequences effective enough to deter those behaviors? Do the instructors employ trauma-informed teaching and do they know who in the class have traumatic histories? Does the school host workshops/seminars/discussions around issues like sexism, domestic violence, or trauma informed courses? These are just a few suggestions that schools ought to consider when inviting women for self-defense classes.

“many martial arts schools have

implemented women only classes..

While it is a good start..

it does not place any responsibility on the men…”

Self-defense is an innate factor for survival. Anyone can defend themselves without having to take a class…Anyone! I’ve even seen videos of prey animals like wildebeest or antelope charging towards their predator. Our first line of protection is our ability to assess a situation and to choose our own safety over the need to be polite or nice. This starts with empowerment and confidence to advocate for ourselves. Self-defense can embody these principles, but it’s rare. To me, the term, “self-defense” sends the message that we are the inherent victim. And that might be accurate as our victimhood started when we were young. Society has imposed a standard of behavior that has made women easy prey. If martial arts schools are really interested in the safety of women, then they need to work with the existing student body. By looking at their own behavior and bias(es), martial arts practitioners can go beyond self-defense techniques: they can foster an environment that is safe not just in their school/studio/dojo, but within their company.

Written by Mia Velez – May 2022

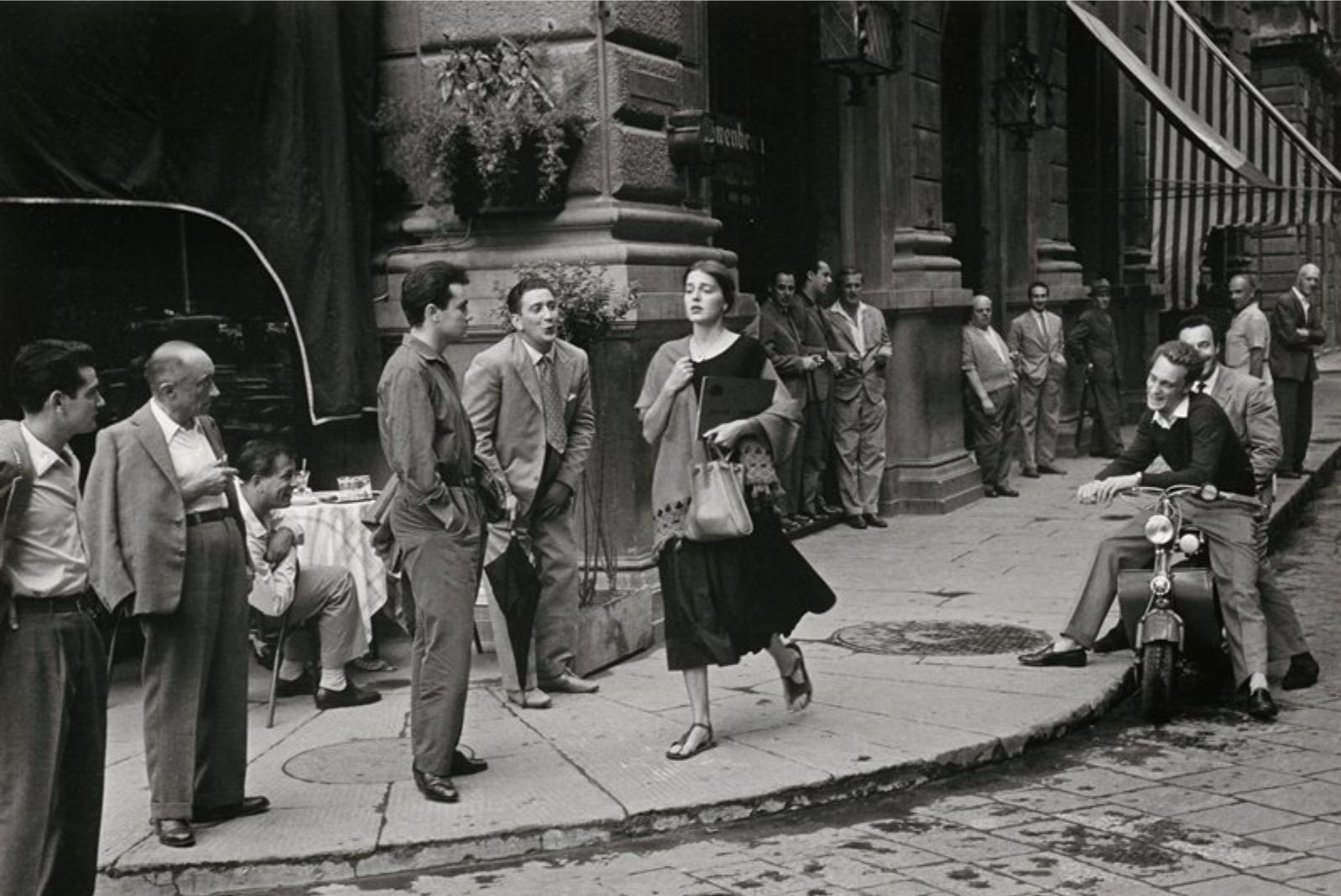

Photo credit: “American Girl in Italy” by Ruth Orkin. Copyright © Ruth Orkin Photo Archive

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/115582/american-girl-in-italy-ruth-orkin